Tajrean

Rahman

It was impossible to exist in the Kingdom of Shaktata in naivety, in self or surroundings. Just as the monsoon season loomed over them, routinely threatening to upend their villages and towns in unforgiving floods, power cycled through the nobility in violent surges, casting out anyone who failed to endure.

With nimble fingers, Ilyas brought a stick of kajal to the corner of his right eye and paused to study himself in the mirror. The evidence of his royal status reflected back at him in abundance: thick, wool rugs lined every inch of his bedroom floor, their vibrant, paisley patterns a fine match to the myriad of colorful book spines stacked along rosewood shelves and window sills.

Even the deceptive simplicity of his green Panjabi suit was made of the highest quality of cotton and handspun silver stitching. Nothing less would be befitting the son of a raja.

Ilyas shut one eye and dragged the kajal along his waterline in a careful sweep. He did the same for his left and examined his handiwork: kajal, was a practice of the Prophet Muhammed, peace be upon him, used to offer a reprieve from the sun’s glare.

Whenever Ilyas lined his eyes like this, the smokey effect of the kajal also served him as a shield against the many prying eyes that tended to follow his every step.

Tonight, it gave him enough fortitude to make the journey from his room to the palace courtyard.

Red and yellow garlands crisscrossed every available pillar, their floral blooms mingling with the heady aroma of doi and crispy fried jilapi. Enormous platters of mishti were laid out in a mosaic of Bengali sweets: golden clusters of ladoo, milky white rasgulla, browned gulab jamun, still warm and glistening in sugar syrup.

The scene was abundant in the visual finery of celebration, but the people in its midst were stiff in their motions, much like dolls play-acting for the royal court. His entrance was met with expectant stares, but he had only eyes for the front of the banquet hall where his father sat beside the representative of the Kausoid nation.

Where the raja was trim but short in figure, their pale-skinned guest towered over them—his girth only part of what made his general presence so overbearing. The Kausoids were a boastful people, every one of them seemingly in competition to be the loudest, or wealthiest, or most vicious.

Arrogance was their only rallying point. They came to Shaktata on a ship from the Northern continent, trussed up in their layers of silk clothing, then complained when the weather was hot or the roads were muddy. Though Ilyas had tracked how their empire had expanded through military force, he also suspected the more pervasive danger was the fact the Kausoids themselves had never understood what it meant to be denied.

“Assalamualaikum,” Ilyas nodded.

There was hardly any acknowledgment before his father turned to the Kausoid and spoke in English, “Bromwell, you remember my son.”

“Yeah,” the Kausoid sliced a piece of jilapi with one of his foreign utensils made of silver. As he inspected the sweet, Ilyas resisted the urge to snatch it away.

Shaktata’s food was meant to be enjoyed by hand. Somehow it made the dining experience more sacred—to hold their nourishment in their own fingertips and marvel at the hands that had played a part in making it. Like the rest of their culture, the Kasoids had only invented ways to dissect and pillage for morsels of their own choosing, leaving everything else in pieces.

Bromwell chewed slowly as he sized up Ilyas, then pointed with his fork, “This is the younger one, yeah? Not as cheerful, this one.”

“Hard to smile when my brother is dead.” Ilyas deadpanned in the man’s native tongue, hating how the harsh consonants made the language more a warning than a way of communication. “You might remember, since you killed him, sir.”

“Pagoler kotta bondokor.” The raja hissed in Bangla. Stop the crazy talk.

Ilyas’ heartbeat quickened as he forced a tight smile. “Shutto kotta bal lage na?” Don’t like hearing the truth?

“He is sorry,” his father said in a rush as he turned to Bromwell.

The Kausoid laughed, “I can handle a little digging.”

He stabbed through another piece of jilapi and suddenly the festering hatred inside Ilyas was all-consuming. In what distorted reality did any of this make sense? Bromwell was an invader to Shaktata—like in every kingdom before, they approached them under the false guise of allyship before quickly turning to stab them in the back. Entire villages had been razed, their waters poisoned and lands salted.

Lutfer, his brother, was dead, and yet the raja could only bow in deference to this pasty-faced man, hoping the inequities of their treaty would be enough to save their people from assured death.

Ilyas began to turn away but he heard Bromwell call after him: “But be careful little prince, there are others who may not share the same humor.”

There was a sickly delight in the man’s pale blue eyes. Ilyas gritted his teeth.

“Then, your father will end up with no heirs for the Shaktata throne.”

✶✶✶

The night air that greeted Ilyas outside the palace was humid, pressing against his face in a sticky embrace. A knot had formed at the base of his throat, but the tears did not come.

Something had irrevocably changed inside him the night he’d learned of his brother’s death. Ilyas had been sleepless as usual with the ongoing tensions of the Kausoid threat. They were hungry for Shaktata’s wealth of minerals and farmland, not in mere trade but complete dominion. It hadn’t been clear at this point if it would’ve been better for the raja to launch an attack or persist with their attempts at negotiating trade terms that would benefit both nations.

At the knock on his door, Ilyas had only needed to look at the messenger’s face for a second before racing down the stairs to find Lutfer’s lifeless body—still bleeding from a bullet made of silver.

Even then, Ilyas had not been able to cry. He had not even been able to call out bhaiya, the Bengali honorific for older brothers. After the numbing shock came a feeling of devastation so agonizing, he could only kneel on the floor. His hand found Lutfer’s and it was the first time the touch had been that of a stranger’s, cold and foreign. Lutfer had only ever been the opposite: the enthusiastic, welcoming sun to Ilyas’ shaded and cagey moon.

Shaktata army generals and advisors had talked his father through the nature of events leading to the Kausoid attack, the potential avenues for diplomacy. They were ill-equipped to fight against the might of an empire, so they decided they would answer Lutfer’s murder with compromise. Rather than a quick extermination, the raja decided on a slower death built on land offerings and land agreements, setting Shaktata on the course for prolonged suffering.

When Ilyas finally rose from his brother’s corpse, he had methodically, carefully, shut off every emotion. Only anger—all-consuming, and still so useless—remained inside him, burning hotter and hotter with each destruction he witnessed on his people, all under control of the Kausoids.

Shaking off his thoughts, Ilyas began to walk back to his room when his ears picked up on a soft murmur. He wondered briefly if he had hallucinated the sounds until he heard it again: a voice of soft, lilting cadences, each word akin to a fleeting musical note that rang out once before it got swallowed by the void.

Grass blades tickled through the openings of his sandals as he made his way through the stretch of farmlands behind the royal palace. That dreamy voice grew louder with each step, an irresistible siren song that drew him beside a tool shed where he observed a curious pairing.

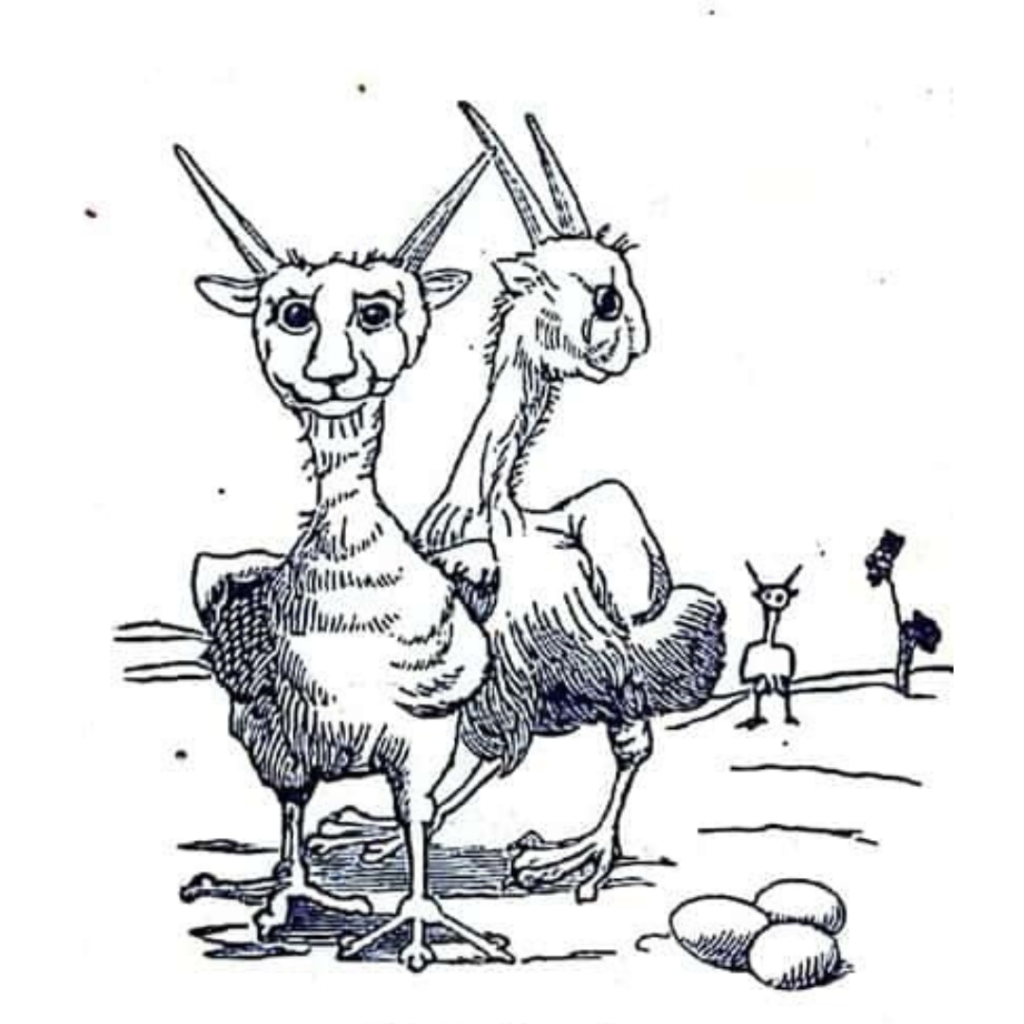

A servant girl in a salwar kameez was leaning against one of the animal pens, shovel in hand with accompanying piles of straw at her feet. Her attention was fixed on a snow-white goose as she sung through an old Bengali nursery rhyme with nonsense words about horned egg-laying mythical creatures:

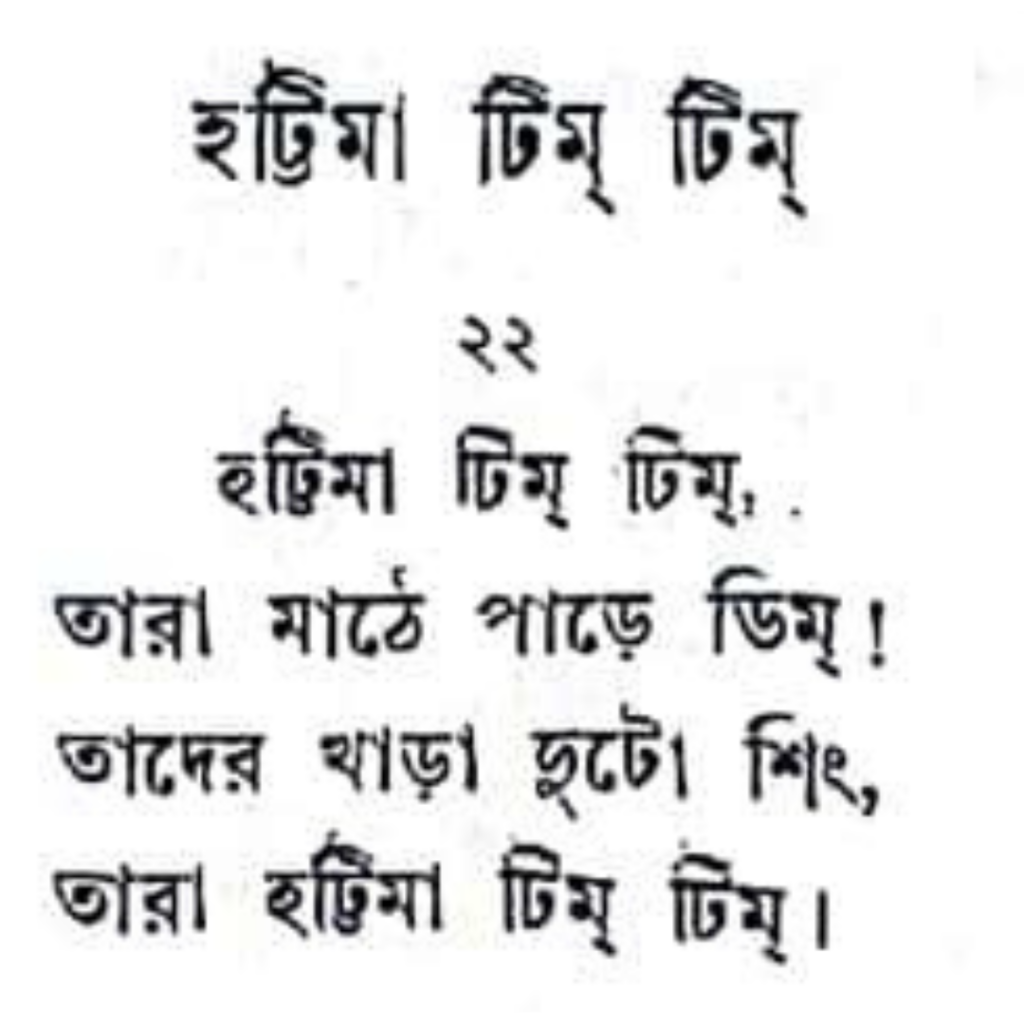

Haattimatimtim,

Tara maathe pare dim.

Tader khara duto shing,

Tara—

The goose honked, cutting her off. She shook her head and chided the animal, “Aharey, let me finish first.”

“Do you think it has met the hattimatimtim?”

Stiffening, the girl whirled in Ilyas’ direction. She gripped her shovel, “This—this was a private conversation.”

“I didn’t mean to interrupt. Truly.” Ilyas affected an appropriately apologetic expression. “I was just curious how one ended up singing to a goose.”

“I…” her voice faltered as she tugged on the folds of her hijab with sudden self-consciousness. “I’ve been tasked with cleaning the goose pens. I suppose it’s inevitable to have their company.”

Her feathered companion honked in confirmation.

For a moment, Ilyas watched her steady her shovel, a solitary figure under the endless, starry night. Then he also grabbed a shovel and joined her, earning an incredulous stare. It felt right somehow—solid, the tangible feel of honest labor. When he’d been younger, the Shaktata nobility used to flock to him with eager compliments and favors, all hoping to ply him with enough flattery to draw him into senseless political machinations.

He mused aloud, “They say the hattimatimtim are made up, but I think the goose would know the truth.”

“You’re putting a lot of faith in an animal that keeps feuding with horses three times its size,” the girl said with a slight smile.

Ilyas’ brow rose, “Tenacious animal.”

“Bokka,” she corrected, which drew out a laugh from him. Silly.

They passed the next few hours trading more stories of dumb animals and nonsensical nursery rhymes amidst their digging. His Panjabi collected several smears but Ilyas was too immersed in conversation to care, completely drawn to how the girl’s brown eyes brightened with her every emotion. He could only spectate at her joy and humor, hoping to bask in even a ray of the feelings she expressed so easily.

When they finished, he found himself asking, “Do you always work through the night?”

“No,” she reached down to smooth her goose’s feathers. “It’s changed since the treaty. Most of the day is spent on the gold mining for the Kausoids, you know. The animals have been abandoned for days now. I wanted to help while the raja sets a better system.”

“He won’t.”

Her eyes widened at his dissent, “You can’t say that.”

“It’s the truth.” Urgency suddenly flared in Ilyas’s chest and he gripped the girl’s hands until their faces leveled. Recognition finally lit in her face.

“Rajputro—”

“Run.” Ilyas said. “You need to leave Shaktata. Take your family, your goose. Tell whoever you need. Go eastward, find safety away from here.”

“I—I,” the girl tried to shake her head. “There were peace talks, I thought things would get better.”

“The Kausoids will kill us,” Ilyas’ lips trembled as he admitted the truth.

“Wallahi, nothing will stop them. I say this after looking the white devils in the eye myself. Please go.”

The girl stumbled with his release, fear stitching her into a new figure in the moonlight. But she managed a nod to him and scooped up her goose before racing away. Ilyas stood by the pen, watching as she disappeared and trusting his message would spread. In another life, he might’ve fought on the battlefield to better honor Shaktata’s glory, but it was impossible to win against an enemy that denied one’s humanity—the sides would always be skewed when they greeted their oppressors with gifts as they sent bullets into their backs.

Ilyas tilted his head skyward. There it was again, the knot of emotion, the unceasing despair in knowing that there was no way to fight back in this moment. Tears spilled down his cheeks as he accepted this was the final death knell of his beloved kingdom.

The servant girl would survive though, in whatever number, some of his people would survive through escape and refuge, building lives outside of the Kausoid’s influence. He may not live to see it, but Shaktata would live on through them. It would have to be enough.

Tajrean grew up as a voracious reader and her addiction has only been further encouraged by the fact she now has adult money for endless books. As a Muslim Bengali-American, she is passionate about writing stories about characters from her background. Previously, Tajrean has written short stories for Tuesday Magazine and authored a bi-monthly Op-Ed column for the Harvard Crimson.

@tajdream